With tax hikes, bulk trade deals and heavy borrowing, the war’s most important long-term economic legacy for New Zealand was to increase both the size of the state and the scale of its intervention in the economy. The effects of this shift are still felt a century later.

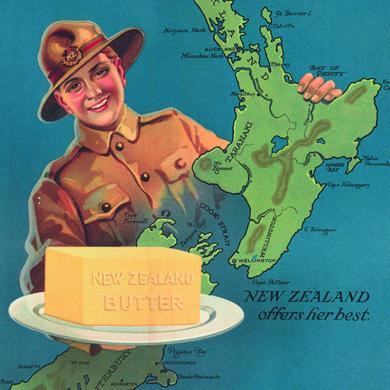

Detail of British First World War poster advertising New Zealand butter. Courtesy of Imperial War Museum © IWM (Art.IWM PST 13684)

The cost of the First World War was counted in more than just loss of life. It disrupted international trade, diverted production, drew manpower away from industry and made unprecedented demands on government expenditure. New Zealand, like the other combatant countries, faced the major challenge of reorganising its resources so as to stay afloat through a long and burdensome war.

How could a country of just over one million people afford to maintain tens of thousands of fighting men on the other side of the world for what turned out to be more than four years? Two cash cows were available for milking: borrowing and taxation. Here we look at the war’s impact on these two revenue sources, and compare them to current economic data.

The war’s most important long-term economic legacy for New Zealand – and many other countries – was to increase both the size of the state and the scale of its intervention in the economy. The twentieth-century trend towards big government began as a response to the sudden shift in nations’ economic priorities on the outbreak of war. The effects of this shift are still felt a century later.

Imperial commandeer

In early 1915 Britain guaranteed it would buy all the frozen meat New Zealand could make available for export for the duration of the war. This arrangement was known as the ‘commandeer’, but in reality little compulsion was needed to persuade farmers to accept guaranteed higher prices for ‘the last round of beef and the last leg of mutton’. The scheme was later extended to wool and dairy products, on equally favourable terms.

Farming remained the mainstay of the New Zealand economy throughout the war, aided largely by the bulk trading deals with Britain. This image showing two men transporting milk cans through the Winterless North on horse-drawn carts dates from the 1910s. Courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-006307-G.

By 1922, when the bulk purchase agreement with Britain ended, a staggering £161 million (equivalent to $14.8 billion in 2015) had been paid out to farmers under its auspices. About 40% of this was for wool, 40% for frozen meat, and most of the rest for dairy produce. Export prices rose by two-thirds between 1914 and 1919, although the quantities exported fell later in the war because of a shortage of shipping.

The combined effect of the commandeer and the diversion of industrial capacity from consumer goods to war production ensured that New Zealand’s trade balance remained positive. For the five years 1914–18, exports totalled £150 million and imports just £115 million. The direction of trade changed significantly. Exports went even more overwhelmingly to Britain, but by 1918 only 37% of imports by value came from Britain, compared with 60% before the war. Both Australia and the United States, from where shipping was much easier and safer during the war, now supplied more than 20% of New Zealand’s imports, which were mainly manufactured products.

Britain continued to receive the majority of New Zealand’s exports until the 1970s, when it joined the European Economic Community. From this period New Zealand diversified the source of its imports, and later the destination of its exports, around the Pacific region. By 2015, Britain had fallen to the fifth largest importer of New Zealand goods, well behind Australia, China, the United States and Japan.

The British government began purchasing New Zealand butter in March 1915. By November 1917 it was purchasing the country's entire exportable output. This British First World War poster showing a woman in khaki uniform advertising the country's butter features a rather pointed caption: 'New Zealand offers her best'. Image courtesy of Imperial War Museum © IWM (Art.IWM PST 13684)

Taxation

Agricultural producers did well under the imperial commandeer, and the government sought to siphon off some of their additional income to help fund war activities. Farmers, along with other recipients of war-related windfalls, were targeted in the coalition national ministry’s first budget in August 1915, which saw the introduction of a graduated income tax. This represents one of the most profound effects of the First World War on the New Zealand public.

Prior to the First World War, income tax had generated very little of the government’s revenue – only 9% in 1914. During the war, income tax revenue increased ten-fold from £540,000 in 1914 to £6.1 million in 1918 (out of the government’s total tax takes of £5.9 million and £10.5 million, respectively). But people still only paid income tax if they earned over £300 (around $42,000 in 2015) – just 12,000 people out of an adult population of about 700,000 paid the tax. A typical plumber earning £150 per year (around $21,000) did not pay income tax. The top income tax rate rose dramatically from 6.67% in 1914 to 43.75% in 1921.

The incomes of agricultural producers and other recipients of war-related windfalls were targeted by the government's tax reforms. The top income tax rate rose dramatically during the war period from 6.67% in 1914 to 43.75% in 1921. This image featured on the cover of the Observer on 13 March 1915, and is courtesy of Papers Past.

Although the changes made to income tax during this period were described by parliamentarians as emergency measures, they have endured – and expanded – in the century since they were introduced.

In 2016 the top income tax rate is 33% on income over $70,000 (or £500 in 1915) – half the rate in the early 1980s. However income tax still makes up a significant proportion of the government’s revenue: $40 billion out of a total $78.7 billion in the year to June 2014. In addition, every income-earner now pays income tax. In 2015 there were 3,213,000 payers of income tax in New Zealand, compared with a total adult population of 3,556,000.

Borrowing

Borrowing money from the British government was a quick way to help pay the bills before tax reform was introduced. The first £2 million loan for war expenses – equivalent to the total public debt created by the New Zealand Wars of the 1860s – won parliamentary approval on 21 August 1914.

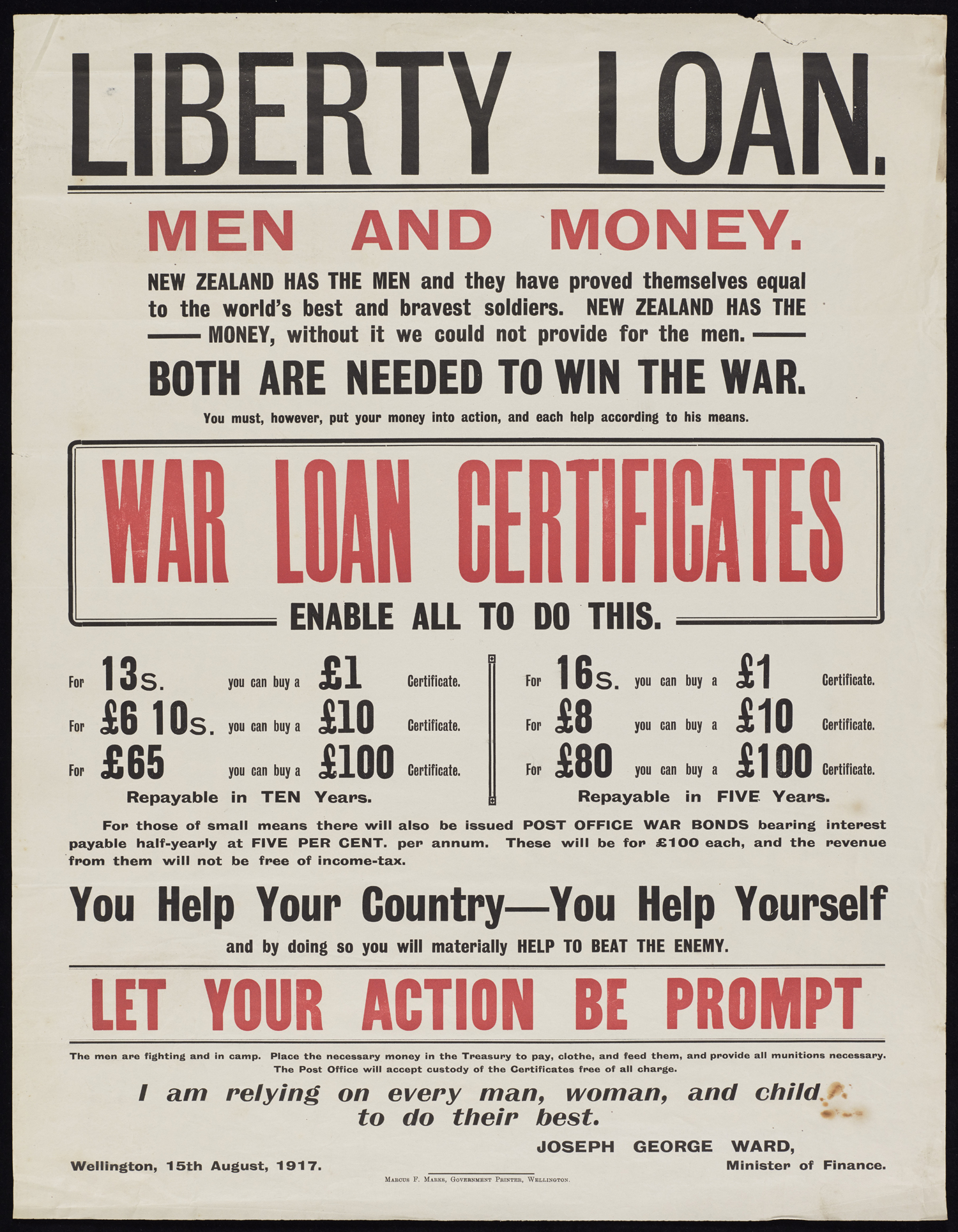

With war expenses set to reach £700,000 per month by mid-1916, the government also began borrowing at home from October 1915. This they achieved by issuing War Loan Certificates and Post Office War Bonds. Though the interest earned was minimal – 0.5% per annum was a typical rate – these loans were usually oversubscribed. The surplus was invested in London at a substantial profit.

'The men are fighting and in camp. Place the necessary money in the Treasury to pay, clothe and feed them, and provide all munitions necessary.' The government implored those at home to help fund New Zealand's war effort. Two-thirds of the 80 million borrowed by the government during the war came from within New Zealand. Image of this August 1917 poster comes courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library. Ref: Eph-D-WAR-WI-1917-01.

A major legacy of the First World War in New Zealand was the public debt, which doubled between 1914 and 1920 to £201 million (equivalent to $16.8 billion in 2015). About £80 million was borrowed for war purposes, two-thirds of it internally. This figure is roughly equal to the total cost of funding and rehabilitating the New Zealand Expeditionary Force up to 1921: £79.3 million.

In 2015 New Zealand’s gross sovereign-issued debt stood at $93.2 billion. While this figure may seem daunting, it represents just 1.2 times as much as the country’s total tax take in the same year ($78.7 billion). By comparison, the burden of New Zealand’s public debt in 1921 (£201 million) was over 12 times that year’s tax revenue of £16 million.

Long after the wartime pressures on the economy ceased, the wartime habit of significant state intervention in the nation’s economic life persisted. The enormous burden of this public debt helped to ensure that ‘emergency measures’ such as a comprehensive income tax endured throughout the twentieth century and beyond.