In an elaborate coronation ceremony at Marton's town hall in September 1915, Joyce McKelvie received a replica crown based on the one worn by English monarchs. Rangitīkei's queen carnival gives us an idea of the great lengths New Zealand communities went to in order to raise funds for the war effort.

Joyce McKelvie - queen of Rangītikei's Queen Carnival (detail), 1915. Courtesy of Te Manawa Museum of Art, Science and History.

‘History has told us of the reign of Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mary, and others, but it remained for Rangitikei to give us a Queen Joyce’ reported the Wanganui Chronicle in September 1915. It was referring to Miss Joyce McKelvie’s success in winning the Rangitīkei queen carnival held over the previous month. The twenty year old daughter of a prominent local landowner had narrowly won the competition ahead of six other contenders representing a combination of geographical areas and local interest groups. Paying two pence per vote, Miss McKelvie’s supporters raised £5,825 of the £15,563 Rangitīkei total.

Queen carnivals became all the rage as patriotic fundraisers in 1915, and Queen Joyce was just one of many winners of the title in cities and townships all over New Zealand. Her scarlet robe and elaborate crown, based upon the St Edward’s crown worn by English monarchs, are in Palmerston North’s Te Manawa Museum. They are tributes to the ingenuity of domestic efforts in support of the Great War, and the complex emotions which underwrote their success.

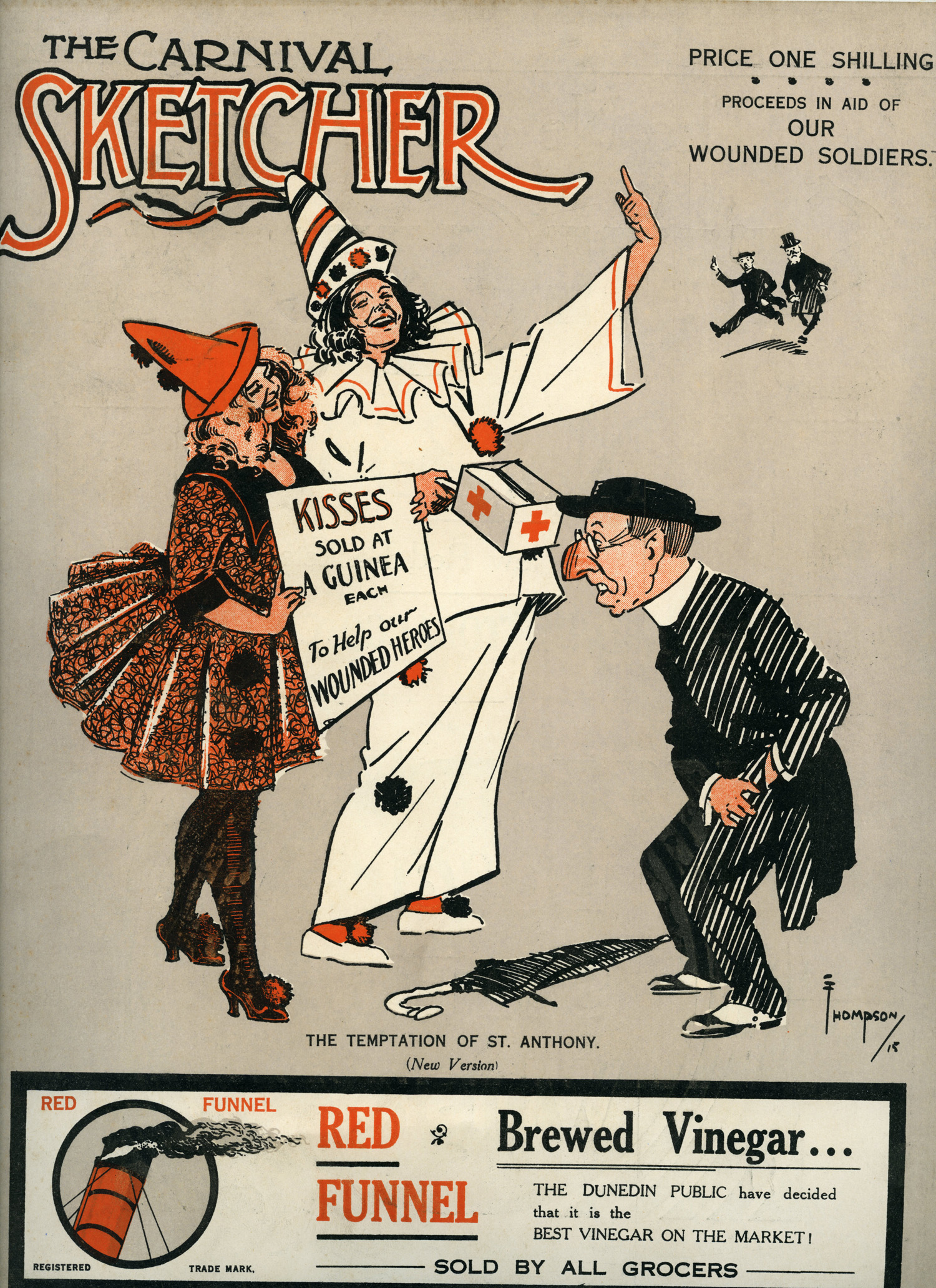

The wartime charity queen carnivals were a form of public drama which referenced tradition, patriotism and loyalty to empire, but also allowed for merriment, ridiculing of authority and challenges to social norms. Young women sold kisses on street corners, ‘khaki-clad maidens’ paraded in processions, carnival books caricatured politicians and local notables were tried in mock courts for various offences. Respectable women allowed themselves to be on public display as potential carnival queens and voted for in coinage, though these were not beauty contests as such – mature married women and local worthies were as likely as pretty young women to be among the candidates.

The Marton firm of Lloyd & Co. made the Joyce McKelvie's crown from sheet brass, glass, velvet and rabbit fur. Image courtesy of Te Manawa Museum of Art, Science and History.

Queen carnivals brought together a whole range of existing fundraising techniques and events in an intensive effort typically lasting for as long as a month. In some of the larger centres, professionals were employed to mastermind events. Individuals such as ‘Professor’ Owen Cardston and Mr William Lints moved around the country in 1915 offering their skills as fundraisers and event organisers. There were bazaars, parades, lotteries, sporting events, concerts; perhaps a ball. In Rangitīkei there was a concert for the ‘Military Queen’ at the local drill hall, various auctions and, most popular of all, a Parisian-style ‘Café Chantant’. This was held on several occasions at the Marton Town Hall, and featured the Marton Brass Band, singers and orchestral entertainment, with a supper room and produce stall staffed by local ladies dressed in pierrot costume. Two of the Rangitīkei queens combined efforts for a ‘day of entertainment in the park’, where revellers could ‘shoot at Kaiser Bill’.

Not all agreed with carnivals as a way of promoting patriotic giving. Queen carnivals reached their peak just as newspapers were publishing lists of the dead and wounded from ‘the Dardanelles’ and sick and wounded men were returning to their home communities. (In the Rangitīkei one of their number, Captain Donald Simpson, promised to donate a photograph of New Zealand men landing at Gallipoli for a carnival auction.) Given the immediacy of suffering and loss, some saw the ‘joyous, reckless, impudent, almost devil-may-care festivities’ as inappropriate. Carnivals were criticised as an inferior form of patriotism, where people expected something in return for giving, even if it was simply entertainment. Carnival raffles, in particular, drew criticism from those churches which most strongly opposed gambling. And the Wellington newspapers alluded to another form of non-engagement with true patriotic spirit: dishonest collectors with jam jars, some of them children, conned unwary members of the public during the lead up to its queen carnival.

Founded in New Zealand as a branch of the British Red Cross, the Red Cross organisation played an important role in providing aid to sick and wounded soldiers, and in raising funds for their welfare. Margaret Tennant’s 'Across the Street, Across the World. A History of the Red Cross in New Zealand 1915-2015' (ISBN 978-0-473-32531-2), has several chapters which cover the role of the Red Cross in wartime, most especially its establishment in New Zealand during the First World War and the immense range of patriotic activity carried out in its name. It is invaluable for insights into women’s voluntary work, wartime patriotism and soldiers’ convalescent homes, and is available from the New Zealand Red Cross for $60.00

On the whole, community engagement prevailed, and even the bereaved were said to be throwing themselves heart and soul into carnival work precisely to distract themselves from sorrowful thoughts. There was comfort to be gained from contributing to the welfare of others’ soldier sons and husbands, and working alongside neighbours experiencing similar grief. For others, fun was permitted in a context where mourning was becoming all too apparent; the release of emotions was encouraged, but it was to be paid for. The strategy was successful: massive amounts were raised at the carnivals, the largest total coming from Auckland, where £251,000 was raised and 21 million votes recorded.

The total from the Rangitīkei queen carnival was much less, but significant enough for a largely rural and dispersed population. And if the Rangitīkei coronation was also on a lesser scale than those held in the four main centres, it was no less attentive to detail in replicating elements of an actual British coronation, minus the sacred elements. ‘A more charming, graceful or dignified Queen of the Realm of Giving it would be impossible to conceive’ said the Wanganui Chronicle of Queen Joyce. The other competing queens were demoted to maids of honour for this grand event, and pages, an orb-bearer and ‘Lord High Chancellor’ featured in proceedings. The coronation saw the transformation of the town hall into a throne room with illuminations, flowers and velvet and gold festoons. It was said to be ‘the most splendid thing ever seen in Marton’.

Elaborate preparations were made for the coronation of Joyce McKelvie (seated centre and wearing a crown). Local seamstresses would have outfitted her retinue of page boys, ladies-in-waiting and courtiers. A local magistrate and barrister lent their wigs for the occasion too. Image courtesy of Te Manawa Museum of Art, Science and History.

Patriotic queen carnivals were at their most popular in 1915. Although they continued in later years, they never reached the same level of popularity and spectacular display. It may have become more difficult to engage in such extravaganzas as the war ground relentlessly on and its consequences became more apparent. It was hard to sustain the emotional drive behind such events over a long period: the disconnect between frivolity and grief may have become too pronounced. And the fashion may simply have passed, as so often happens with such events.